Since the beginning of the year the deportation prison Bässlergut, at the Otterbach border in Basel, is being enlarged with a second building. With a discusion weekend from the 6th to the 8th of October 2017, taking place around the Bblackboxx, right next to the construction site of the new building, we wanted to share our criticism about this project with as many people as possible.

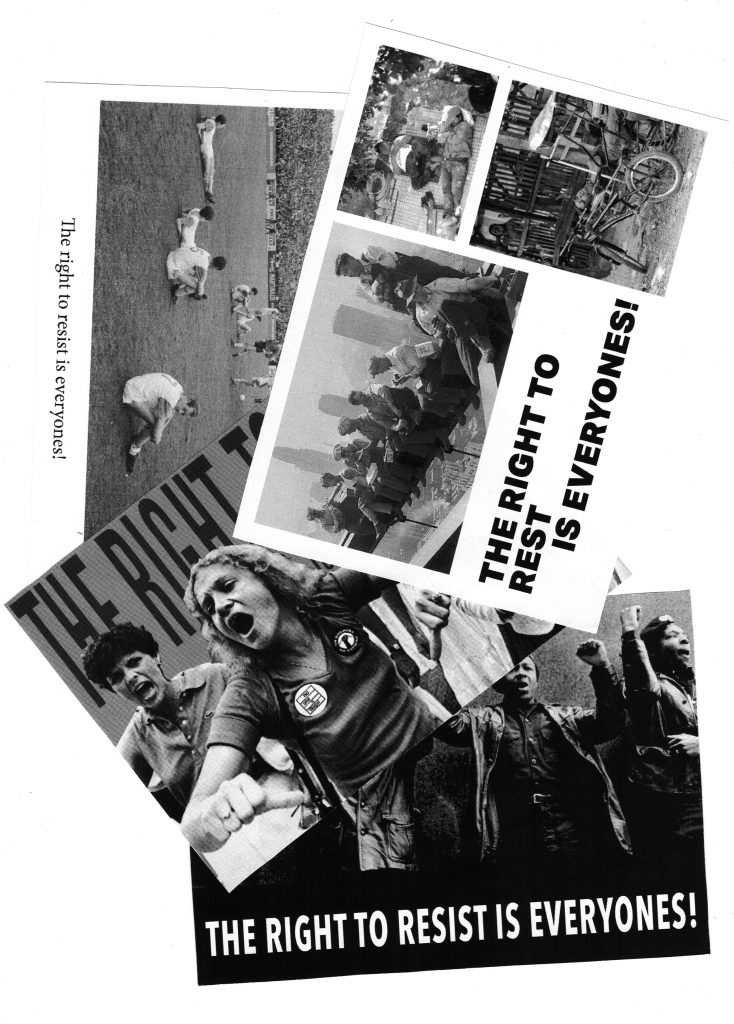

We wanted to exchange thoughts on these relations, our utopias and ways to resist. At the same time being present at this site should become part of the resistance against prisons, borders and repression. The event was organized by individuals who had been involved in these topics already an found together through it.

Diverse critics on the conditions that manifest in Bässlergut

The program started on Friday evening with a well attended NO-Lager-tour around the reception- and processing-center (Empfangs- und Verfahrenszentrum EVZ) the already present deportation-prison Bässlergut I and the construstion site of Bässlergut II. The knowledge of the day-to-day conditions behind these walls that had been collected in conversation with detainees was shared. This was followed by an input on the developments and relationships between the asylum- and justice system. This input made clear that the new building Bässlergut II is an expression of a development which will lead to a future where more migrants and destitute people will be imprisoned – who often are the same, going back and forth from deportation prison to penal prison in the new building.

The program started on Friday evening with a well attended NO-Lager-tour around the reception- and processing-center (Empfangs- und Verfahrenszentrum EVZ) the already present deportation-prison Bässlergut I and the construstion site of Bässlergut II. The knowledge of the day-to-day conditions behind these walls that had been collected in conversation with detainees was shared. This was followed by an input on the developments and relationships between the asylum- and justice system. This input made clear that the new building Bässlergut II is an expression of a development which will lead to a future where more migrants and destitute people will be imprisoned – who often are the same, going back and forth from deportation prison to penal prison in the new building.

With a general criticism of the prison as an institution throughout the last 200 years the Saturday session was opened. In small groups the subjective sense of security was discussed. It became apparent that a strong sense of social security in ones circle of friends or in political contexts was important. Whereas the structural security e.g. having a Swiss passport and the privileges that come with it played a less important role. Can one fear starvation when one has never starved? One of the participants described their privileges also as dependencies that can be withdrawn when one doesn‘t stick to the rules of the game (freedom of movement, various social services).

Through the initiative of a group of people who regularly visit prisoners in Bässlergut and prisoners themselves, a visit to the inmates took place to show solidarity. For a lot of the participants this was a new and important experience. And also the inmates were happy about this support. A regular visitor of Bässlergut prisoners said that he had never seen as many people in the visiting room of the prison before. This collective visit has led to organized, monthly visits (Agenda, S.70). Parallel to the prison visit, an introduction in the historical development of the idea and practice of custody was given. Under this term in Switzerland there exists a years long or lifelong imprisonment that can be ordered by psychiatrists with the help of computer programs. The discussion that followed in small groups was dedicated to the question of how a helpful practice (in solidarity) with mentally ill people should look like. A central point of the discussion was the criticism that psychiatric clinics dehumanize and try to “normalize” patients as well as the lack of knowledge and discomfort when dealing with mentally ill people in ones environment. To be able to help those affected by mental illness, one needs specialized knowledge and a social environment sensitive to their needs.

Later in the afternoon a brief story was told of how prisons in the U.S.A are currently being privatized. Prisons have become a lucrative business for private companies. Various international companies (including European ones) compete on this market, doing lobby work to establish more restrictive laws, exploiting prisoners as a cheap workforce.

Later in the afternoon a brief story was told of how prisons in the U.S.A are currently being privatized. Prisons have become a lucrative business for private companies. Various international companies (including European ones) compete on this market, doing lobby work to establish more restrictive laws, exploiting prisoners as a cheap workforce.

The day ended with a film-screening by Kino Vagabund: Fragments of “Vol spécial” by Fernand Melgar and the short movie “Einspruch VI” by Rolando Colla. After the two movies, a controversial discussion began: Are consternation and identification with the victims of the deportation regime the right conditions for a political fight? Are the films demonstrating structural relations and taking a clear position to these? And, what use is it to watch, when one should spring into action?

On Sunday morning, a migrant without papers explained his way through the Swiss camps, prisons and psychiatries and how he ended up in a political environment, fighting for his own rights. He then described how an active resistance against the present system and the practice and exchange with like-minded people allowed him to have a long-term perspective in Switzerland.

Early in the afternoon, questions of privileges, guilt and solidarity were being defined and discussed in a workshop. One person without papers, that had been arrested for several months, said, that to him, visits in prison were a strong gesture of solidarity. At the same time he criticized that in Switzerland the equalization of the terms solidarity with the terms charity and charitable work is often being made. In some groups, there were also discussions about whether or not privileged people should use their privileges in a fight based on solidarity. This could be dangerous: It could reproduce the structures that generate these privileges. Another option would be to fully refuse structures that produce privileges, but this goes with a loss of possibilities to support others.

Food for thoughts about resistance

Our critical presence close to the new prison Bässlergut II, the deportation prison Bässlergut I and the EVZ was creating a form of resistance. There were many lively discussions, in which different topics were treated and critically examined. The presentations filled with interesting content and the broad spectrum of critique showed many structures and practices that need to be fought. It remained difficult to find ways how to translate this knowledge and exchange into a practice of resistance. In this way the weekend was raising indeed the wish to act, but didn’t really open up new perspectives of action. Instead it left some participants with a feeling of powerlessness. The question how and where shared knowledge can be transformed into a practice could have more importance in the planning of a further event like this one.

Several directly affected people insisted on the fact, that authentic and effective resistance requires a bigger willingness for actions that question also the life of one’s own and bring about risks (like money or prison sentences or the loss of privileges). Maybe it is indeed true, that people who are not yet living in a perilous situation, should take resistance more seriously and don’t let themselves stop by the risks that come along with it.

What use is it to watch, when one should spring into action?

During the mobilization process for the event we were often confronted with superficial questions about the deportation policy, but during the weekend the discussions were almost exclusively lead in a principal anti-capitalist mindset. The predominant discourse in this society on deportation policy in the style of “it is indeed a human tragedy, but nonetheless not all of them can come here” was not an issue during the weekend. This is on the one hand a comfortable basis for deeper discussions, on the other hand it can make us forget, how much every kind of alternative to the current migration regime requires a fundamental change of this society and can only be understood on this basis. If migration policy should change, the whole political and economical system must change, which also implicates a fundamental change of society.

Commonalities and exclusions

With around two hundred participants despite the cold and rainy weather, the event was quite well attended. People from the EVZ were present, although they were not participating much at the different activities, even tough they have been informed beforehand about the topics and possibilities of translations. The question arises if the framework of presentations with discussions is suitable for an exchange like this. Anyway, thanks to the excellent and permanent food supply the breaks were used to eat together and have more discussions in small groups.

With around two hundred participants despite the cold and rainy weather, the event was quite well attended. People from the EVZ were present, although they were not participating much at the different activities, even tough they have been informed beforehand about the topics and possibilities of translations. The question arises if the framework of presentations with discussions is suitable for an exchange like this. Anyway, thanks to the excellent and permanent food supply the breaks were used to eat together and have more discussions in small groups.

Despite the spicy topic, the police appeared only two times openly on the spot. But still the repression had its effects on the weekend. Some interested people were on the other side of the prison walls and some others didn’t dare to attend the event because of the danger of prosecution and arrest.

Outlook

On the 30th of October there was a further meeting at which the discussions focused more on perspectives and possibilities of resistance. At this meeting the necessity of a long term, open and transparent organization as well as the direct intervention in the public discourse and conditions became evident. Regular public exchange meeting are planned. And also other kinds of actions and discussions (like the collective visits in the prison Bässlergut I since the weekend) continue in a public way.

The construction of Bässlergut II continues until 2019 and probably the conditions materialised by it will persist beyond this date. An infrastructure that is being built, will be used in consequence. The joined resistance in discussions and actions against it remains a necissity!