The photographs were taken during an official guided tour within the prison Bässlergut. Glances at the reception cell, the production room, the yard, the courtroom, the isolation cell, and the prison’s own kiosk. Then, we are back at the big steel gate separating the two worlds from each other. We were not allowed to take pictures of prisoners or personnel. What remains are empty rooms and the traces of human beings imprisoned.

Category: Bässlergut

Everyday life in the deportation prison – A conversation in Bässlergut with two detainees

The following interview took place in the Bässlergut deportation prison during the official visiting hours. Standing in front of the large prison gates, we press a red button and via intercom give the names of the people we want to visit. The first door opens; before being allowed through the second we have to wait again; ultimately, we are let in and after a few metres we enter the overheated entrance area of Bässlergut. Take off the winter jacket, hand in the ID-card, deposit our bags, fill in the registration form, go through the turnstile and pass the metal detector. As always, we are taken one-by-one to the visitors’ room where we take our seats and wait until finally, we are five of us at the table. Although we all already know each other, the two detainees we’ll be interviewing are rather mistrustful at first. They show this by not only wanting to know why we wish to interview them but also who we work for and whether we are affiliated to any (political) group or association. The interview is very risky for the two detainees, as they are subject to the capriciousness of the wardens. Recognising this, we would like once again to thank both for allowing us to publish our conversation.

You‘re about to have a level 1 deportation.1 Will you resist this?

B: Yes, I‘m being subjected to a Level 1 deportation. I can’t cope with going through all the levels again and then getting kicked out a third time so violently. No, I really don’t want that. I don’t know, when exactly I will be deported. I will only hear about 2 to 3 days beforehand. It doesn’t bring much to resist anyway; it would only defer the deportation by 2 to 3 weeks.

N: The problem is that we are just seen as foreigners. That we’re also humans gets forgotten.

B: I grew up here and now I‘m being deported and can’t stay with my child. What I really want is to live here, look after my family and see my child grow up! Actually, I never wanted to put kids onto this fucking world. But now I have one and have to leave. I won’t be able to see how he develops, how he eats, speaks or walks for the first time.

What’s your everyday life look like here in Bässlergut?

B: At 7:15 the guards open the door to our cell and at 17:00 it’s closed again. There are three of us living in our cell. We have a TV there. In addition, there’s a common room on our floor with a kitchen and a large table, but only two chairs. It’s not cosy there at all.

N: Being able to go out helps the time pass. Some go out, a few stay inside. Twice a day we can go into the courtyard, once for an hour and once for two hours.

What about the food?

B: Breakfast is at 7:15 and we have something to eat again at 11:00 and at 17:00. Second-helpings are out. Once we asked the guards if we could order a pizza and pay for it ourselves. „Fuck you,“ was the answer.

N: A small kiosk is open once a week where we can buy food, drinks, cigarettes and other things. But they are completely overpriced: An M-budget chocolate bar costs about Fr. 2.00.

N: A small kiosk is open once a week where we can buy food, drinks, cigarettes and other things. But they are completely overpriced: An M-budget chocolate bar costs about Fr. 2.00.

B: I work 2½ hours a day and can hardly buy anything with what I earn!

And what about the work?

N: In the evening, the prison wardens come and ask who wants to work the next day. On Monday, Wednesday and Thursday the working hours are from 8:00 to 10:30 and on Tuesday and Friday from 14:00 to 16:30.

B: Two to three people sit at each work-table. We are not allowed to talk. You can only drink water from a tap in the toilet. We’re not allowed to drink water while working.

What sort of work do you do?

B: At the moment, we’re mainly doing things for Christmas, for example, assembling different packages and gluing pieces together. When they’re finished, the packages are then sent to Belgium, where they are filled with various things. From there they go on to China. But I don’t know who the order is for.

N: For the two and a half hours we work we get Fr. 7.50 each.

B: Last week my wife and child came to visit me when I was working. At the reception they asked to see me, but nobody came to tell me that my family was here. So, they left again. When later I found this out later, I asked the guard why he hadn’t informed me. Seeing my wife and child is more important to me than shitty Fr.7.50! „Those are the rules: When you agree to work you have to work.“ was the answer I got.

N: Withdrawing the allowance to work is sometimes used as a form of punishment as this means you aren’t able to earn any money.

Do you work?

B: Yes, I work regularly. But not because of the money. No, the only reason I work is that I sometimes need to get some peace. Otherwise all around me people are always listening to music, talking on the phone or talking to other people. By going to work, I can escape the hubbub for a short period of time.

N: No, I don’t work anymore. Three months ago, I broke a small carton box while working. It was only about as big as an A4-sized page …

B: That can happen; it‘s all happened to all of us some time!

N: … I got bunker-arrest for five days. I haven’t worked since then. I don’t want to risk having to go there again.

Can you tell us something about the bunker? What’s it like?

N: It’s an isolation cell used for solitary confinement. In my case, for breaking a small cardboard box at work. During the time in the bunker I was only allowed to walk in the courtyard once a day and on my own; the rest of the time I spent isolated in a room with a small window and a TV. After five days, I was finally able to return to my cell.

What kind of medical care do you have?

What kind of medical care do you have?

B: There are two doctors you can go to. One is not helpful at all. He treats us aggressively. We speak different languages which often leads to misunderstandings. We are as unimportant to them as we are to the guards. You can tell by how they talk to you and how they deal with you in general. One detainee in our cell swallowed a lot of shampoo once. He had mental problems and hadn’t eaten for a long time, but he smoked like a chimney. Do you think the guards arrived straight away when we called for help? No way, they only got here after three-quarters of an hour, although they could have made it in five minutes. That shows how we aren’t taken seriously here.

N: Two weeks ago, I asked the psychiatrist who treated me two years ago, to come over because I wasn’t well. However, the prison guards told me that this wouldn’t be possible and that I wasn’t even allowed to ask.

Walking past the turnstile to the visitors‘ room, one can see on the right-hand side a cupboard full of various medicines. Do you get the medication you need? And what medicines do you get?

B: Yes, we can get medication. All the medicines we take have already been dissolved in water. It isn’t possible to get medication in the original packaging. I bet there‘s Temesta in it as well. When I asked if I could get my medicine in its original packaging, I was told, „Shut up, you shit foreigner.“ Since then, I have stopped taking medicines because I see what happens to everyone else: either they calm down and sleep or they become aggressive. By the way, the same thing happens after dinner: We all go to sleep afterwards. That‘s not normal! Or do you go to sleep every time you eat? There is certainly some sort of tranquilizer in the food.

How do you get on with each other?

B: We spend most of the time on our own – each of us in our own part of the cell. Everyone tries to cope with their problems by themselves. Especially if someone has been badly treated, then he can become very aggressive. Then it is better to leave him alone for the time being. Added to that, we have difficulties communicating with each other, as we speak so many different languages.

Are there any collective forms of resistance?

B: Once somebody went on a hunger strike for seven days. Then the guards put him in the bunker and gave him some medication. Even in our cell, we’ve thought a few times about going on a joint hunger- or work-strike and we already started planning one once. But there are always a few detainees who don’t want to join in. I can understand that too: If you smoke, you just need to go to work. That‘s why such plans to resist fail.

N: Actually, one could say that the only way to survive here is to try to stay stable. Because they want that: to break us mentally.

Do you feel any solidarity from outside the walls of Bässlergut?

B: No; and, if so, then only through visits from outside. Anyone who doesn’t have any visitors doesn’t feel any solidarity. Once you‘re in jail, you‘re stigmatised, you don’t have any friends any longer. When you‘re in jail, suddenly all your friends are gone and nobody comes to visit you. That‘s the way it is…

Gegen wen richtet sich eure Wut?

N: When I was outside, I didn’t know what the deportation prison is like. Now I‘ve been here for four months. What’s done here to people, doesn’t happen anywhere else. If I ever get out, I’ll come back to Switzerland and demolish this prison. Since being here this has become my goal.

B: As a foreigner, you can do little to change your situation. Even if you‘re born here and have a Swiss passport, you‘ll always be a foreigner. This Blocher, who earns millions every year and stirs up resentment against foreigners. Who works for him? Who cleans his toilet? And he says “shit foreigners”! In this world, the mightier one always wins. That’s reality. Switzerland is said to be neutral. But who supplies weapons to the rest of the world? Switzerland is said to be neutral. But that‘s just not true. Switzerland is a police state. Once the prosecution has decided what’s going to happen to you, it’s closing time. Is your lawyer a member of the SVP? Then it’s closing time. They can offend us foreigners as much and as often as they want. We’re here and just have to shut up.

«I don’t expect anything much from life anymore»

Fahim sits in front of us and nods his head in a friendly way. We take this to mean we can start the interview. The young man doesn’t seem to care too much about what we do in our lives, how we make our money or if we belong to an organisation. Fahim tells us he has been in the deportation prison Bässlergut for some months now pending deportation. Before this he had spent several years in various other prisons – firstly in a juvenile detention centre and then in adult prisons. He says he has been in prison for far too long and is sure he must have more than finished his sentence by now.

When asked how the everyday life in an ordinary prison differs from that in a deportation centre like Bässlergut, he names the opportunity to work. In prison Fahim was responsible together with eight other inmates for preparing lunch and dinner for 140 people.

It was a strenuous job, and in the evening, I knew how hard I had worked.

For the 6½ hours a day that he worked, Fahim received 22 Swiss francs. He managed to save some money so that he doesn’t now have to work in Bässlergut.

Conditions in the deportation prison

Fahim tells us that the inmates in Bässlergut get on well with each other in general, even if communication is difficult, as most speak either English, French or Arabic but not German. He spends most of his time sleeping and doesn’t have much to do with the other prisoners or the wardens. He only sees the latter when he gets medication (for his gastric acid reflux), a shaver or food. Otherwise he’s by himself a lot. Until recently Fahim shared the cell with another inmate, but now he has been deported, Fahim has the cell to himself.

That doesn’t matter to me. On the contrary. I prefer to be alone. I don’t care what the mood in the prison is or how the others are doing. I’ve had enough of it all.

Ten people are currently detained in Fahim’s wing of the centre and all should be deported as soon as possible. The wing has single, two-, four- and eight-person cells, as well as a common-room with table football, a kettle for making tea, a table and three chairs.

Just yesterday an observation camera was installed in the common-room. Probably because some inmates smoked cigarettes while playing table football.

Unlike prison, the food here is awful, Fahim tells us. “Sometimes there is only soup and a piece of bread in the evening”. Everyone eats on their own in their cell.

Impending deportation

The first time Fahim heard that he was going to be deported was in a letter. This listed his crimes and the grounds for the deportation. Although Fahim put the letter aside, he tells us, he never forgot it. In fact, he always believed that he would be freed after having served his sentence. He received the letter at a time when he was on the run, having absconded from an open prison. But after a few months he turned himself in to the police. Because he had absconded he wasn’t allowed to return to an open prison but had to go to a detention centre instead, where he spent a further year.

The first time Fahim heard that he was going to be deported was in a letter. This listed his crimes and the grounds for the deportation. Although Fahim put the letter aside, he tells us, he never forgot it. In fact, he always believed that he would be freed after having served his sentence. He received the letter at a time when he was on the run, having absconded from an open prison. But after a few months he turned himself in to the police. Because he had absconded he wasn’t allowed to return to an open prison but had to go to a detention centre instead, where he spent a further year.

At the detention centre you‘re in your cell for 23 hours a day and are only allowed out for one hour. It wasn’t until I wrote to the authorities that I was allowed to leave the detention centre.

Why he had to stay in the detention centre for such a long time, he still can’t explain. After the detention centre and following his trial Fahim spent a further two years and nine months in prison.

The authorities there are the worst when it comes to applying for early release on grounds of good behaviour or for holiday permits. I was neither granted leave, nor was I released early for good conduct. But that didn’t just happen to me, it was the same for most of the others too.

Two weeks before his release, he was told that he would be moved to Bässlergut in order to prepare for his deportation. Ever since then, Fahim has been fighting to be released, but a request to the Court of Appeal for discharge was denied. Although Fahim – as he tells us – hasn’t entirely given up hope, it’s diminishing day-by-day. Asked what he would do if he were actually released, Fahim says he would go to Sri Lanka for up to three months.

After that I would return to Europe, either to Germany or Austria, where I would have to stay at least five years before I could enter Switzerland again.

He tells us that he already has contacts in Austria. He knows a boxing club there and has already sent them videos of him boxing. The club would like to take him and would help him look for a job.

Prison & deportation as seen by Fahim

For Fahim a B-permit means much the same as an F- or C-permit. His younger brother and his father both have a C-permit; his mother a B-permit. Why his mother hasn’t got a C-permit despite being employed and having lived long in Switzerland, he doesn’t know. Like him, his older brother is in custody and is also threatened with deportation. Five years ago, a friend of his was deported to the Ivory Coast. „He’s in bad shape there, because all his relatives are in Switzerland“. Fahim thinks that a prison sentence may sometimes make sense, especially if it can help you gain an insight into your behaviour. When we ask Fahim if he would have given himself a prison sentence, he replies,

I have committed many crimes; even the police don’t know about many of them. Altogether, I think 4½ years in prison are warranted. Somehow or other I’ve earned such a long prison term.

However, he finds it difficult to accept that, after having served his prison sentence, someone should then be deported. He cannot understand how one can take everything – even family and friends – away from a person. Furthermore, he finds it absurd to invest a lot of money in integrating somebody into society, only to subsequently deport him. Fahim points out that he has changed a lot over the years and learned a great deal, but this doesn’t seem to interest the authorities. Although he has been living in Switzerland for 17 years and has no ties to Sri Lanka, he should be deported there.

I’ve paid my debt to society, served my sentence in prison. Now I am waiting for a miracle.

Politics and perspectives

Before he went to prison Fahim hadn’t thought much about prisons or deportation. „As long as you don’t have anything to do with them, the whole thing seems far away“. Fahim doesn’t know whether in the future he wants to fight against repressive measures such as imprisonment or deportation. He assumes that people would then point a finger at him and call him a criminal. To go to a demo would take a lot of courage for him, as they often end up with a confrontation with the police. His friends aren’t politically active either.

When I‘m released, I don’t want to do anything but work, box and spend time with my family. I don’t expect anything great from life anymore.

This article is based on a conversation the authors held with Fahim. For Fahim it was important that the article covered everything that we talked about and not just focus on one main point. Before the interview Fahim was offered the opportunity to narrate freely, but he preferred to answer questions which the authors had prepared in advance. The authors of this article have been arguing against Bässlergut for a long time. Their fundamental criticism of the prison is based on their rejection of the rule of one over others.

WEek END BÄSSLERGUT

Since the beginning of the year the deportation prison Bässlergut, at the Otterbach border in Basel, is being enlarged with a second building. With a discusion weekend from the 6th to the 8th of October 2017, taking place around the Bblackboxx, right next to the construction site of the new building, we wanted to share our criticism about this project with as many people as possible.

We wanted to exchange thoughts on these relations, our utopias and ways to resist. At the same time being present at this site should become part of the resistance against prisons, borders and repression. The event was organized by individuals who had been involved in these topics already an found together through it.

Diverse critics on the conditions that manifest in Bässlergut

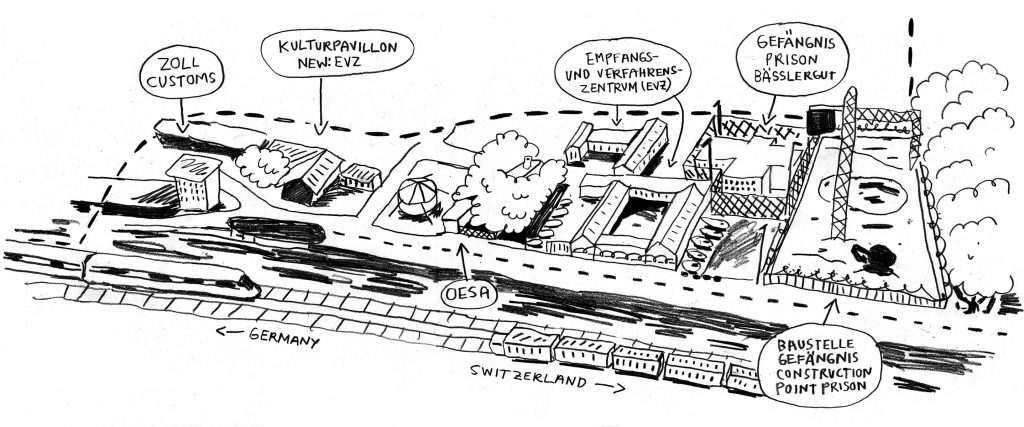

The program started on Friday evening with a well attended NO-Lager-tour around the reception- and processing-center (Empfangs- und Verfahrenszentrum EVZ) the already present deportation-prison Bässlergut I and the construstion site of Bässlergut II. The knowledge of the day-to-day conditions behind these walls that had been collected in conversation with detainees was shared. This was followed by an input on the developments and relationships between the asylum- and justice system. This input made clear that the new building Bässlergut II is an expression of a development which will lead to a future where more migrants and destitute people will be imprisoned – who often are the same, going back and forth from deportation prison to penal prison in the new building.

The program started on Friday evening with a well attended NO-Lager-tour around the reception- and processing-center (Empfangs- und Verfahrenszentrum EVZ) the already present deportation-prison Bässlergut I and the construstion site of Bässlergut II. The knowledge of the day-to-day conditions behind these walls that had been collected in conversation with detainees was shared. This was followed by an input on the developments and relationships between the asylum- and justice system. This input made clear that the new building Bässlergut II is an expression of a development which will lead to a future where more migrants and destitute people will be imprisoned – who often are the same, going back and forth from deportation prison to penal prison in the new building.

With a general criticism of the prison as an institution throughout the last 200 years the Saturday session was opened. In small groups the subjective sense of security was discussed. It became apparent that a strong sense of social security in ones circle of friends or in political contexts was important. Whereas the structural security e.g. having a Swiss passport and the privileges that come with it played a less important role. Can one fear starvation when one has never starved? One of the participants described their privileges also as dependencies that can be withdrawn when one doesn‘t stick to the rules of the game (freedom of movement, various social services).

Through the initiative of a group of people who regularly visit prisoners in Bässlergut and prisoners themselves, a visit to the inmates took place to show solidarity. For a lot of the participants this was a new and important experience. And also the inmates were happy about this support. A regular visitor of Bässlergut prisoners said that he had never seen as many people in the visiting room of the prison before. This collective visit has led to organized, monthly visits (Agenda, S.70). Parallel to the prison visit, an introduction in the historical development of the idea and practice of custody was given. Under this term in Switzerland there exists a years long or lifelong imprisonment that can be ordered by psychiatrists with the help of computer programs. The discussion that followed in small groups was dedicated to the question of how a helpful practice (in solidarity) with mentally ill people should look like. A central point of the discussion was the criticism that psychiatric clinics dehumanize and try to “normalize” patients as well as the lack of knowledge and discomfort when dealing with mentally ill people in ones environment. To be able to help those affected by mental illness, one needs specialized knowledge and a social environment sensitive to their needs.

Later in the afternoon a brief story was told of how prisons in the U.S.A are currently being privatized. Prisons have become a lucrative business for private companies. Various international companies (including European ones) compete on this market, doing lobby work to establish more restrictive laws, exploiting prisoners as a cheap workforce.

Later in the afternoon a brief story was told of how prisons in the U.S.A are currently being privatized. Prisons have become a lucrative business for private companies. Various international companies (including European ones) compete on this market, doing lobby work to establish more restrictive laws, exploiting prisoners as a cheap workforce.

The day ended with a film-screening by Kino Vagabund: Fragments of “Vol spécial” by Fernand Melgar and the short movie “Einspruch VI” by Rolando Colla. After the two movies, a controversial discussion began: Are consternation and identification with the victims of the deportation regime the right conditions for a political fight? Are the films demonstrating structural relations and taking a clear position to these? And, what use is it to watch, when one should spring into action?

On Sunday morning, a migrant without papers explained his way through the Swiss camps, prisons and psychiatries and how he ended up in a political environment, fighting for his own rights. He then described how an active resistance against the present system and the practice and exchange with like-minded people allowed him to have a long-term perspective in Switzerland.

Early in the afternoon, questions of privileges, guilt and solidarity were being defined and discussed in a workshop. One person without papers, that had been arrested for several months, said, that to him, visits in prison were a strong gesture of solidarity. At the same time he criticized that in Switzerland the equalization of the terms solidarity with the terms charity and charitable work is often being made. In some groups, there were also discussions about whether or not privileged people should use their privileges in a fight based on solidarity. This could be dangerous: It could reproduce the structures that generate these privileges. Another option would be to fully refuse structures that produce privileges, but this goes with a loss of possibilities to support others.

Food for thoughts about resistance

Our critical presence close to the new prison Bässlergut II, the deportation prison Bässlergut I and the EVZ was creating a form of resistance. There were many lively discussions, in which different topics were treated and critically examined. The presentations filled with interesting content and the broad spectrum of critique showed many structures and practices that need to be fought. It remained difficult to find ways how to translate this knowledge and exchange into a practice of resistance. In this way the weekend was raising indeed the wish to act, but didn’t really open up new perspectives of action. Instead it left some participants with a feeling of powerlessness. The question how and where shared knowledge can be transformed into a practice could have more importance in the planning of a further event like this one.

Several directly affected people insisted on the fact, that authentic and effective resistance requires a bigger willingness for actions that question also the life of one’s own and bring about risks (like money or prison sentences or the loss of privileges). Maybe it is indeed true, that people who are not yet living in a perilous situation, should take resistance more seriously and don’t let themselves stop by the risks that come along with it.

What use is it to watch, when one should spring into action?

During the mobilization process for the event we were often confronted with superficial questions about the deportation policy, but during the weekend the discussions were almost exclusively lead in a principal anti-capitalist mindset. The predominant discourse in this society on deportation policy in the style of “it is indeed a human tragedy, but nonetheless not all of them can come here” was not an issue during the weekend. This is on the one hand a comfortable basis for deeper discussions, on the other hand it can make us forget, how much every kind of alternative to the current migration regime requires a fundamental change of this society and can only be understood on this basis. If migration policy should change, the whole political and economical system must change, which also implicates a fundamental change of society.

Commonalities and exclusions

With around two hundred participants despite the cold and rainy weather, the event was quite well attended. People from the EVZ were present, although they were not participating much at the different activities, even tough they have been informed beforehand about the topics and possibilities of translations. The question arises if the framework of presentations with discussions is suitable for an exchange like this. Anyway, thanks to the excellent and permanent food supply the breaks were used to eat together and have more discussions in small groups.

With around two hundred participants despite the cold and rainy weather, the event was quite well attended. People from the EVZ were present, although they were not participating much at the different activities, even tough they have been informed beforehand about the topics and possibilities of translations. The question arises if the framework of presentations with discussions is suitable for an exchange like this. Anyway, thanks to the excellent and permanent food supply the breaks were used to eat together and have more discussions in small groups.

Despite the spicy topic, the police appeared only two times openly on the spot. But still the repression had its effects on the weekend. Some interested people were on the other side of the prison walls and some others didn’t dare to attend the event because of the danger of prosecution and arrest.

Outlook

On the 30th of October there was a further meeting at which the discussions focused more on perspectives and possibilities of resistance. At this meeting the necessity of a long term, open and transparent organization as well as the direct intervention in the public discourse and conditions became evident. Regular public exchange meeting are planned. And also other kinds of actions and discussions (like the collective visits in the prison Bässlergut I since the weekend) continue in a public way.

The construction of Bässlergut II continues until 2019 and probably the conditions materialised by it will persist beyond this date. An infrastructure that is being built, will be used in consequence. The joined resistance in discussions and actions against it remains a necissity!

The expansion of Bässlergut

The Bässlergut Penal and Deportation Prison is being expanded with a second building. The new building will provide 78 places for regular punishment, which means that the “old” building will now have 73 places for pre-deportation detention. With the expansion of Bässlergut, the current developments of increasing control, surveillance, and the categorization of people are demonstrated.

The history of Bässlergut

Bässlergut Prison was named after the Bässler family, which until 1962 farmed the estate as farmyard Otterbach. After the land was purchased by the state, a reception center for asylum seekers was established in 1972 and in the year 2000, the present-day Bässlergut deportation prison with 48 prison cells. As a result, the history of the Bässlergut property is relatively young and should be understood here as a product of a policy that excludes and criminalizes people who don’t conform to the norm. This is evident in the growing political will of Switzerland to categorize people -in this case migrants- more consistently into desired (useful) and undesirable (useless) people and to quickly get rid of the latter. This categorization of migrants went together with their criminalization, which was pushed forward with the 1994 Foreigner’s Statute (Ausländergesetzrevision 1994). At that time, a majority of the voting population advocated the integration of the coercive measures found in the Foreigner’s Act, which legalized imprisonment as a preparation for deportation (administrative detention). This development has been driven not only in Switzerland, but also internationally. Thus, readmission agreements have strengthened cross-border cooperation in the fight against people without permits.1 While the legal foundations for the expansion of imprisonment was created, so was the bureaucratic burden of conducting the implementation of expulsions. As a result, the preparatory period lasted longer, while the political agenda also increased the number of people to be deported.

The places reserved in the prisons for deportations – ‘Schallenmätteli’ for men and ‘Waaghof’ for women – were no longer suited for the new situation: new places had to be created. These demands for the expansion of the prisons were associated with the (spatial) devision of prisoners. Since people in deportation prison are in administrative detention (so not deprived of freedom due to a crime), the conditions of detention should differ from those in prison or pre-trial detention, according to the reasoning. In order to make this distinction between prisoners, the construction of separate prisons was suitable. Even when in reality the conditions of imprisonment hardly differ, (see below) this critique of deportation prisons was used to legitimize new prisons.2 Nevertheless, in 2011, there was a change in the use of a station for a regular prison sentence in Bässlergut I, due to a lack of space in the Waaghof prison. In 2012 and 2013, an additio- nal station was put into operation. Since then, Bässlergut I has accommodated 30 prisoners in pre-deportation detention and 43 prisoners in the ‘criminal’ prison. At the same time, the current reception and procedural center (Empfangs – und Verfahrenszentrum (EVZ), which offers space for up to 500 people, was opened from the original receiving center for asylum seekers. These two developments were accompanied by increased privatization. In both places, the private company Securitas is responsible for security. In the EVZ, the Austrian company ORS is also experimenting with profitorial support. In prison, the inmates worked for 6.50CHF/2h for private companies in de facto forced labor for pro t. Since the Spring of 2017, the expansion of Bässlergut has been under construction, providing space for 78 more prisoners and will be operational by the end of 2020. The current penal places will then be used again for the purpose of deportation, whereby the separation and categorization of the prisoners is again respected. Consequently, new prison cells are currently being developed which will have to be filled with humans in the future and further de ne the repressive developments of the last two decades.

Camp with special laws

In the context of the Asylum Reform 2016, the EVZ will be converted into a federal camp in the future. In Switzerland, 16 federal camps are planned with space for 5,000 people. A distinction is made between procedures, departure, and special centers. In the departure center, deportation is prepared, with at least 100 days planned and mostly concerns people who are to be deported to other European countries under the Dublin Agreement. The 2 planned, special centers are specifically for so-called ‘renegade’ asylum seekers, whereby it remains undefined from which unadjusted behavior is regarded as unruly. In processing centers, surveys, legal counseling, return counseling, as well as accommodation and employment of migrants is managed. The time of these procedures is to be broken down to 140 days, thus reducing the timespan for complaints from 30 days to 10 days.3 The concentration of asylum seekers anchored to the Asylum Law Revision 2016 should make the handling of future applications “efficient, cost-efficient, and fair” (Federal Council of Switzerland).4 This efficiency that is spoken of, means in reality that migrants will be concentrated and isolated in a camp. Through the acceleration of the procedures, the categorization of migrants into desired and undesired is implemented in a more radical and reckless way. For it will be more dif cult to meet the criteria, as well as to resist a decision. Additionally, readmission agreements with third countries will be linked to economic agreements (see Fiasko Nr. 1/2017), which will allow forced deportation from Bässlergut I to be carried out more smoothly. The second point of the more favorable procedures is to be achieved by the centralization of personnel and infrastructure. For migrants in the process, this means everyday life spent within the camp. This practical limitation is additionally reinforced by barbed wire, surveillance cameras and exit controls. The spatial proximity of the various buildings also reflects the reality: from the processing center directly to the neighbouring deportation prison, from the Prison II because of illegal residence via a builtin corridor directly into Bässlergut I. In order to implement the last core criteria of the “fair” reforms, so-called independent jurists were highlighted. The fact that their independence is doubtful has already been stated several times. The short appeal periods, the proximity of the lawyers to the workers of the immigration of ce, and lump payments are only a few critical factors.5 However, what is rarely addressed is the basic context

Beginning with the mere existence of a ‘foreigner’s law.’ A law which has existed since 1934 and is directed only at a specific social group. It is therefore in its existence racist and exclusive. Just like other parts of Swiss law, it is created to protect the privileges of individuals and their property. If one speaks of the rights of migrants, they are always granted only if an economic bene t can be drawn from it, or if Switzerland wants to maintain the image of a nation in which human rights are unconditionally adhered to. We refer here to a frequent objection, namely, that human rights are also taken into account in the asylum system. In reality, it is much more their instrumentalization. Thus, NGOs such as the Swiss Refugee Aid, Caritas Switzerland, Amnesty International, the Salvation Army, HEKS, Schweizerische Arbeitshilfswerk SAH, and the Organization of Swiss Jewish Welfare (Der Verband Schweizerischer Jüdischer Fürsorgen/Flüchtlingshilfen (VSJF) support this humane policy farce.6 On a human, individual level, their support services can in uence the situation of certain individuals and this can also be valued. When looking at a structural level, however, the problem behind this support is quickly apparent. With support, whether legal or everyday, the SEM can cover its administration of migrants into a humanitarian farce. We see the current developments, such as the imprisonment (in the procedural center or jail), the compulsion to work in employment programs, isolation and death (whether eeing or fainting in asylum structures), as part of a „humane asylum policy“. Volunteer work/social work within the prede ned structures of the camp, also when they mean well, are still part of the camp. They will, on the one hand, help in the public debate to legitimize the camp as a humane place. On the other hand, they assume a de-escalating function, in which they help the “embedded” soothe and de ect from reality.

Solidarity is extremely important, as well as individual support, but self-reflection should be carried out about one’s own role, and ways should be found to break the camp structures and thus, the isolation and lack of self-determination. NGO’s, such as Swiss Refugee Aid, are an example for all those organizations that do not address the fundamental problems and provide guidance in shaping the management of misery. The new structuring of Swiss migration policy is therefore aimed at concentrating, isolating and managing migrants more intensively. The descriptive keywords of “efficient, cost-efficient, and fair“ thus try to sell a camp policy as democratic and fair. In reality, however, it describes a suppressive and exploitative system. Finally, it is important to note that these are not new tendencies. The only thing new about the latest developments is that the infrastructure for the already existing processes of migration policy is now being built. This infrastructure will make it even harder to move, organize and live independently. As the agencys aggressiveness increases, the fullfillment of regulations will be even more difficult – and will be more consistent with deviations.

The revival of imprisonment

The current developments do not only affect people without valid residence permits. With the extension of Bässlergut, prison places for people with regular prison sentences are also being expanded. These places are reserved for short prison sentences of up to one year. The new sanctioning law, which will come into effect in January 2018, provides for easing the possibility of short-term imprisonment of less than 6 months. This is to be taken into account when there is a risk that the perpetrator will be sentenced again or on the basis of the financial situation of a convicted person not being able to comply with the punishment imposed. This conversion from a monetary punishment to a prison sentence is often the case of a conviction based on illegal residence. The prison in our society takes a deterrent function. For many people, threats and the possibility of a deprivation of freedom and the consequences, for a time determined by the state, to be completely alienated and robbed of any autonomy, is the reason not to defend themselves against the existing order and to instead accept their own position and function in this society.

On the term ‘Camp’

The Federal Camps fulfill the characteristics of all camps. This characteristic entails the spacial concentration of a specific social group as well as the subordination and control of the group. This is the result of either the goal of reintegration into the society or the definite exclusion/expulsion from it. Camps are not limited to migrants, but diverse social groups. For example, in Switzerland, there are camps for people with disabilities, people with mental illnesses, or elderly people; with the same function of exclusion from a low economic value.

Of course, the consequences of a prison sentence and the perspectives at the end of a penal term differ for people with Swiss papers from those of people without Swiss papers, but the social function of the prison remains the same. Resistance Since its construction, Bässlergut has been fought by various people from inside and outside. Rebellions within the prison’s everyday life in the form of insulting the staff, hunger strikes, and refusal to work while different networks of the prison practice are documented and vehemently criticized. In 2008, some prisoners set a re, expressing their anger. As a result, they were severely sanctioned (i.e. a with a ban on visits). In 2010, it went public that an underage man was held in isolation naked.7 The then director had to leave his position. After that, many things were “politically correct,” since harassment and oppression were inherent in imprisonment. Furthermore, prisoners within Bässlergut empower themselves, even when the psychological pressure and scope for action within the walls are a heavy burden. Hunger-strikes, threats, denial of compulsory exit and / or prison work are now part of daily resistance. There is an attack on the practice of isolation (people are still partially naked), as well as poor food and inadequate medical care. All this is known through talks with imprisoned people. In addition, small and large demonstrations have been taking place for years in front of Bässlergut, paint attacks, and reworks symbolized the solidarity with the prisoners. Bässlergut developed into a place in Basel where people expressed their resentment against the existing system, but also where the state sent its „friend and helper“ in battle march and thus demonstrated its power. In 2015, a demonstration against the Basel-based CONEX military exercise in front of Bässlergut led to a violent conflict between some demonstrators and the cops, with the latter being decisively attacked. In 2016, various attempts were made to directly prevent deportations by manipulating the entrance gate and blocking the entrance. In addition, there were several prison walks, where the people behind and in front of the bars expressed their mutual solidarity and short dialogues were possible. Since the construction of Bässlergut II began in March 2017, there have been various acts of sabotage on small and large companies, which are directly involved in the construction process and enrich it. A demonstration with the end point of Bässlergut, was dissolved by the cops after a failed attempt to kettle the people. However, critical discussions, information events and practical actions are not restricted, but are rather widespread. Bässlergut has become a place that brings together many people and diverse forms of resistance in order to make a fundamental criticism of current developments and social conditions. This is because the three interrelated levels of the administration of migrants in the federal camp and imprisonment in separate prisons, the increase in imprisonment penalties, and the role of humanitarian organizations, which are clearly evident in the Bässlergut project. In addition to the place where migrants arrive inside deportation prison, which in turn is connected to a corridor to the prison system. The infrastructure is co-ordinated, as is its social function: people who do not conform to the norm, who do not provide the economic bene t, or even defend themselves, are criminalized, concentrated and imprisoned. Due to the broad dimension of the developments around Bässlergut, a range of resistance forms become possible and necessary. Whether autonomous support structures, dissemination of a basic criticism, pressure on executive actors or other forms of displeasure – is important that we are loud, creative and disruptive!

We are two women who grew up in Basel – and have grown up with the privileges of having the Swiss passport. Through personal contacts and our own experiences, we are angry at the prevailing conditions and the society of which we ourselves are a part.

The deportation business

An angry knock at the door of his cell in Bässlergut Prison tells him that they’ve come to deport him. Aren* prepares to resist. The four policemen have to drag him out of the small room when he refuses to leave, kicking and beating him in the process, until he finally submits and is cuffed at his hands and feet, cutting off the blood flow. They put a helmet on his head and bring him to a car waiting in front of the prison. The car takes him from Basel to Geneva Airport where a level-4 special deportation flight to Liberia is waiting for him.

The second deportation

Once he arrives at the capital Monrovia, Aren is taken to an interview with the Liberian department of immigration. In a last-ditch effort to avoid deportation, he says that he is not a Liberian citizen at all. He says he’s actually from Nigeria. The ambiguity of his statements cause confusion in the tiny office, which apart from Aren comprises only one representative from the Liberian department of immigration; the Swiss officers are barred from sitting in on the talks. The representative finally refuses to accept Aren without clear identification. The officers, denied the opportunity of deportation without the necessary documents, fly him back to Switzerland. Once they touch down in Geneva they tell him he’s free to go. He is taken to the refugee center in Sissach where a doctor gives him a checkup. Injuries on ear, leg, knee, and hands lead the doctor to request an examination at the hospital nearby. But that will never happen: Aren is woken once again by a knocking on his cell and they bring him back to Bässlergut Prison. He is told that this time he’ll be deported to Nigeria. A second deportation in such a short time is unrealistic, Aren is sure of that. He is almost past the 18-month deportation time limit. According to Swiss law he’s allowed to go free after this period. And he is sure that no one believes that he really is Nigerian, because when he applied for asylum he clearly stated that he is Liberian. The Swiss department for immigration did not believe him and initiated an inquiry with a Nigerian delegation of experts who stated that they did not believe Aren to have Nigerian citizenship.

Aren’s hopes were disappointed; a week later Aren is deported to Nigeria in a joint flight commissioned by Frontex. There is no further interview with the Nigerian embassy, but replacement documents (Laissez-passer) were issued all the same based on third party statements.

Migration partnerships

According to the asylum statistics by the State Secretariat for Migration (SEM), Aren is one of 101 persons who were deported to Nigeria in 2016. Compared to other African countries Nigeria ranks highest, followed by Tunisia with 59 deportations.

2011 Switzerland and Nigeria concluded a migration partnership. The contract binds Nigeria through a readmission agreement to accept also involuntary deportations.

2011 Switzerland and Nigeria concluded a migration partnership. The contract binds Nigeria through a readmission agreement to accept also involuntary deportations.

The Swiss Government has already signed similar partnerships with Tunisia, Kosovo, Serbia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina and last October negotiations have begun with Sri Lanka. The aim of these partnerships is “to improve cooperation in the field of migration as well as to reduce illegal migration and its negative consequences.” (Art. 100 FNA). Accompanying this definition, the Foreign Nationals Act includes potential agreements, border control, deportations and job-related further trainings.

How these agreements are going to be implemented is unclear. Applications for scrutinizing the several thousand documents concerning the migration partnership agreement between Switzerland and Nigeria are still in progress. The few press releases by the Federal Council give scant insight into the partnership.One example is a pilot project aimed at cooperation between police forces which enabled stage-deployments of Nigerian police officers on Swiss soil. Furthermore, the migration partnership between Switzerland and Nigeria is being lauded for facilitating “innovative migration projects” in cooperation with the food company Nestlé. A statement released by the Federal Council on July 2, 2014 says: “The cooperation between the FOM (now called State Secretariat for Migration SEM) should be named as a good example. This private- and public-sector partnership supports the professional education of thirteen young men and women. The best five will be accepted for an internship in Switzerland in the summer of 2013.” When compared to the amount of deportations, that number seems like an absurd nuance with which the migration partnership and it’s cooperation with Nestlé is being legitimized.

Nestlés profit with water

Nigeria’s water resources are dwindling and the droughts caused by climate change make the land less and less arable. The consequences of these developments are growing conflicts surrounding the extant areas and migratory shifts from the countryside to the cities, which often do not have adequate infrastructure or enough work.

It is exactly from this scarcity that Nestlé profits. For years now, the Swiss company has been buying the rights to water supplies in Nigeria. In the official statement for “Pure Life”, a brand of bottled water they produce, it says that with their help jobs are created and access to clean drinking water is made possible. The fact that most people in Nigeria cannot afford to buy bottled water is omitted. The privatization of water supplies does not assist the access to clean drinking water it denies it.

Peter Brabeck-Letmathe, former CEO and current president of the board of directors of Nestlé, said in reaction to allegations of profit oriented water productions: “Water is a grocery item. It should have a market value like any other. I personally believe that to appreciate water, it should have a market value so that we aware that it costs something.”

It is significant that the cooperation with Nestlé whose privatization of water supplies in Nigeria is well documented, and who disregards all existential realities, would be mentioned as an example for success of the migration partnership. It’s distinctive of an endemic hypocrisy to give privileges such as free movement, protection, and job opportunities to a select minority while repressing a majority that goes along with it. The migration partnership between Switzerland and Nigeria does not only institutionalize an inhumane deportation policy, much worse it supports the logic of a for-profit economy that endangers the daily lives of a large part of the population, which in turn results in migration.

Level 1: The person to be deported has agreed to return voluntarily. He/she is accompanied by the police to the airplane; the return takes place without accompaniment;

Level 2: The person to be deported has not agreed to a vountary return trip. Generally he/she is accompanied by two plainclothes police officers. If necessary handcuffs are used;

Level 3: It is to be expected that the deported person is going to physically resist, but the transport with a regular flight is possible. The deported person is accompanied by two plainclothes police officers. During the deportation handcuffs and other captivation-resources as well as physical force can be used;

Level 4: It is to be expected that the deported person is going to perform heavy physical resistance; A special flight is necessary for the transport. Each deported person is accompanied by at least two police officers. The same compulsion-resources as in level 3 can be applied.

Level 1 conforms to the colloquial „voluntary departure“, Level 2 to the „controlled deportation“ and Level 3 plus 4 to the „special flight“.

Source

This text was written after an encounter in the deportation-prison with the person mentioned. The author of this text doesn‘t know about the conditions of the person who was being deported: After the deportation all contact got interrupted.

- Bottled Life – Nestlés Geschäfte mit dem Wasser (Dokumentarfilm von Urs Schnell, 2012)

- Wem gehört das Wasser? (Dokumentarfilm von Christian Jentzsch, 2013)