The Bässlergut Penal and Deportation Prison is being expanded with a second building. The new building will provide 78 places for regular punishment, which means that the “old” building will now have 73 places for pre-deportation detention. With the expansion of Bässlergut, the current developments of increasing control, surveillance, and the categorization of people are demonstrated.

The history of Bässlergut

Bässlergut Prison was named after the Bässler family, which until 1962 farmed the estate as farmyard Otterbach. After the land was purchased by the state, a reception center for asylum seekers was established in 1972 and in the year 2000, the present-day Bässlergut deportation prison with 48 prison cells. As a result, the history of the Bässlergut property is relatively young and should be understood here as a product of a policy that excludes and criminalizes people who don’t conform to the norm. This is evident in the growing political will of Switzerland to categorize people -in this case migrants- more consistently into desired (useful) and undesirable (useless) people and to quickly get rid of the latter. This categorization of migrants went together with their criminalization, which was pushed forward with the 1994 Foreigner’s Statute (Ausländergesetzrevision 1994). At that time, a majority of the voting population advocated the integration of the coercive measures found in the Foreigner’s Act, which legalized imprisonment as a preparation for deportation (administrative detention). This development has been driven not only in Switzerland, but also internationally. Thus, readmission agreements have strengthened cross-border cooperation in the fight against people without permits.1 While the legal foundations for the expansion of imprisonment was created, so was the bureaucratic burden of conducting the implementation of expulsions. As a result, the preparatory period lasted longer, while the political agenda also increased the number of people to be deported.

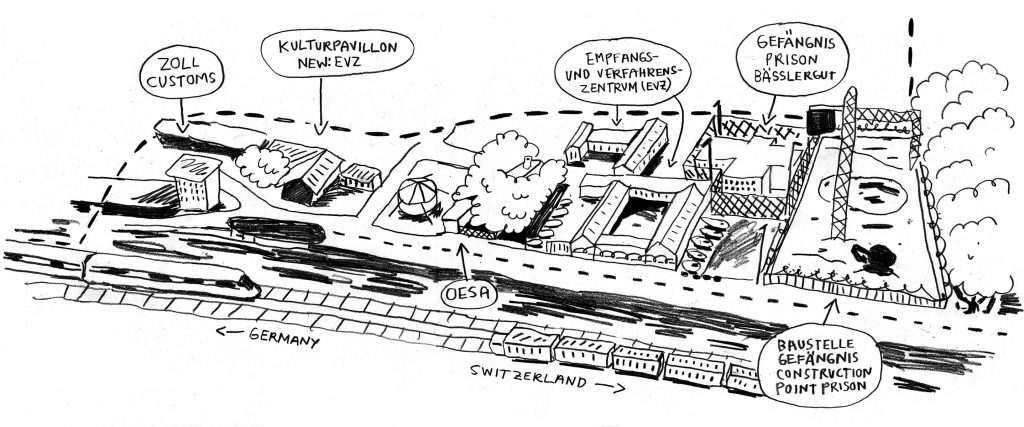

The places reserved in the prisons for deportations – ‘Schallenmätteli’ for men and ‘Waaghof’ for women – were no longer suited for the new situation: new places had to be created. These demands for the expansion of the prisons were associated with the (spatial) devision of prisoners. Since people in deportation prison are in administrative detention (so not deprived of freedom due to a crime), the conditions of detention should differ from those in prison or pre-trial detention, according to the reasoning. In order to make this distinction between prisoners, the construction of separate prisons was suitable. Even when in reality the conditions of imprisonment hardly differ, (see below) this critique of deportation prisons was used to legitimize new prisons.2 Nevertheless, in 2011, there was a change in the use of a station for a regular prison sentence in Bässlergut I, due to a lack of space in the Waaghof prison. In 2012 and 2013, an additio- nal station was put into operation. Since then, Bässlergut I has accommodated 30 prisoners in pre-deportation detention and 43 prisoners in the ‘criminal’ prison. At the same time, the current reception and procedural center (Empfangs – und Verfahrenszentrum (EVZ), which offers space for up to 500 people, was opened from the original receiving center for asylum seekers. These two developments were accompanied by increased privatization. In both places, the private company Securitas is responsible for security. In the EVZ, the Austrian company ORS is also experimenting with profitorial support. In prison, the inmates worked for 6.50CHF/2h for private companies in de facto forced labor for pro t. Since the Spring of 2017, the expansion of Bässlergut has been under construction, providing space for 78 more prisoners and will be operational by the end of 2020. The current penal places will then be used again for the purpose of deportation, whereby the separation and categorization of the prisoners is again respected. Consequently, new prison cells are currently being developed which will have to be filled with humans in the future and further de ne the repressive developments of the last two decades.

Camp with special laws

In the context of the Asylum Reform 2016, the EVZ will be converted into a federal camp in the future. In Switzerland, 16 federal camps are planned with space for 5,000 people. A distinction is made between procedures, departure, and special centers. In the departure center, deportation is prepared, with at least 100 days planned and mostly concerns people who are to be deported to other European countries under the Dublin Agreement. The 2 planned, special centers are specifically for so-called ‘renegade’ asylum seekers, whereby it remains undefined from which unadjusted behavior is regarded as unruly. In processing centers, surveys, legal counseling, return counseling, as well as accommodation and employment of migrants is managed. The time of these procedures is to be broken down to 140 days, thus reducing the timespan for complaints from 30 days to 10 days.3 The concentration of asylum seekers anchored to the Asylum Law Revision 2016 should make the handling of future applications “efficient, cost-efficient, and fair” (Federal Council of Switzerland).4 This efficiency that is spoken of, means in reality that migrants will be concentrated and isolated in a camp. Through the acceleration of the procedures, the categorization of migrants into desired and undesired is implemented in a more radical and reckless way. For it will be more dif cult to meet the criteria, as well as to resist a decision. Additionally, readmission agreements with third countries will be linked to economic agreements (see Fiasko Nr. 1/2017), which will allow forced deportation from Bässlergut I to be carried out more smoothly. The second point of the more favorable procedures is to be achieved by the centralization of personnel and infrastructure. For migrants in the process, this means everyday life spent within the camp. This practical limitation is additionally reinforced by barbed wire, surveillance cameras and exit controls. The spatial proximity of the various buildings also reflects the reality: from the processing center directly to the neighbouring deportation prison, from the Prison II because of illegal residence via a builtin corridor directly into Bässlergut I. In order to implement the last core criteria of the “fair” reforms, so-called independent jurists were highlighted. The fact that their independence is doubtful has already been stated several times. The short appeal periods, the proximity of the lawyers to the workers of the immigration of ce, and lump payments are only a few critical factors.5 However, what is rarely addressed is the basic context

Beginning with the mere existence of a ‘foreigner’s law.’ A law which has existed since 1934 and is directed only at a specific social group. It is therefore in its existence racist and exclusive. Just like other parts of Swiss law, it is created to protect the privileges of individuals and their property. If one speaks of the rights of migrants, they are always granted only if an economic bene t can be drawn from it, or if Switzerland wants to maintain the image of a nation in which human rights are unconditionally adhered to. We refer here to a frequent objection, namely, that human rights are also taken into account in the asylum system. In reality, it is much more their instrumentalization. Thus, NGOs such as the Swiss Refugee Aid, Caritas Switzerland, Amnesty International, the Salvation Army, HEKS, Schweizerische Arbeitshilfswerk SAH, and the Organization of Swiss Jewish Welfare (Der Verband Schweizerischer Jüdischer Fürsorgen/Flüchtlingshilfen (VSJF) support this humane policy farce.6 On a human, individual level, their support services can in uence the situation of certain individuals and this can also be valued. When looking at a structural level, however, the problem behind this support is quickly apparent. With support, whether legal or everyday, the SEM can cover its administration of migrants into a humanitarian farce. We see the current developments, such as the imprisonment (in the procedural center or jail), the compulsion to work in employment programs, isolation and death (whether eeing or fainting in asylum structures), as part of a „humane asylum policy“. Volunteer work/social work within the prede ned structures of the camp, also when they mean well, are still part of the camp. They will, on the one hand, help in the public debate to legitimize the camp as a humane place. On the other hand, they assume a de-escalating function, in which they help the “embedded” soothe and de ect from reality.

Solidarity is extremely important, as well as individual support, but self-reflection should be carried out about one’s own role, and ways should be found to break the camp structures and thus, the isolation and lack of self-determination. NGO’s, such as Swiss Refugee Aid, are an example for all those organizations that do not address the fundamental problems and provide guidance in shaping the management of misery. The new structuring of Swiss migration policy is therefore aimed at concentrating, isolating and managing migrants more intensively. The descriptive keywords of “efficient, cost-efficient, and fair“ thus try to sell a camp policy as democratic and fair. In reality, however, it describes a suppressive and exploitative system. Finally, it is important to note that these are not new tendencies. The only thing new about the latest developments is that the infrastructure for the already existing processes of migration policy is now being built. This infrastructure will make it even harder to move, organize and live independently. As the agencys aggressiveness increases, the fullfillment of regulations will be even more difficult – and will be more consistent with deviations.

The revival of imprisonment

The current developments do not only affect people without valid residence permits. With the extension of Bässlergut, prison places for people with regular prison sentences are also being expanded. These places are reserved for short prison sentences of up to one year. The new sanctioning law, which will come into effect in January 2018, provides for easing the possibility of short-term imprisonment of less than 6 months. This is to be taken into account when there is a risk that the perpetrator will be sentenced again or on the basis of the financial situation of a convicted person not being able to comply with the punishment imposed. This conversion from a monetary punishment to a prison sentence is often the case of a conviction based on illegal residence. The prison in our society takes a deterrent function. For many people, threats and the possibility of a deprivation of freedom and the consequences, for a time determined by the state, to be completely alienated and robbed of any autonomy, is the reason not to defend themselves against the existing order and to instead accept their own position and function in this society.

On the term ‘Camp’

The Federal Camps fulfill the characteristics of all camps. This characteristic entails the spacial concentration of a specific social group as well as the subordination and control of the group. This is the result of either the goal of reintegration into the society or the definite exclusion/expulsion from it. Camps are not limited to migrants, but diverse social groups. For example, in Switzerland, there are camps for people with disabilities, people with mental illnesses, or elderly people; with the same function of exclusion from a low economic value.

Of course, the consequences of a prison sentence and the perspectives at the end of a penal term differ for people with Swiss papers from those of people without Swiss papers, but the social function of the prison remains the same. Resistance Since its construction, Bässlergut has been fought by various people from inside and outside. Rebellions within the prison’s everyday life in the form of insulting the staff, hunger strikes, and refusal to work while different networks of the prison practice are documented and vehemently criticized. In 2008, some prisoners set a re, expressing their anger. As a result, they were severely sanctioned (i.e. a with a ban on visits). In 2010, it went public that an underage man was held in isolation naked.7 The then director had to leave his position. After that, many things were “politically correct,” since harassment and oppression were inherent in imprisonment. Furthermore, prisoners within Bässlergut empower themselves, even when the psychological pressure and scope for action within the walls are a heavy burden. Hunger-strikes, threats, denial of compulsory exit and / or prison work are now part of daily resistance. There is an attack on the practice of isolation (people are still partially naked), as well as poor food and inadequate medical care. All this is known through talks with imprisoned people. In addition, small and large demonstrations have been taking place for years in front of Bässlergut, paint attacks, and reworks symbolized the solidarity with the prisoners. Bässlergut developed into a place in Basel where people expressed their resentment against the existing system, but also where the state sent its „friend and helper“ in battle march and thus demonstrated its power. In 2015, a demonstration against the Basel-based CONEX military exercise in front of Bässlergut led to a violent conflict between some demonstrators and the cops, with the latter being decisively attacked. In 2016, various attempts were made to directly prevent deportations by manipulating the entrance gate and blocking the entrance. In addition, there were several prison walks, where the people behind and in front of the bars expressed their mutual solidarity and short dialogues were possible. Since the construction of Bässlergut II began in March 2017, there have been various acts of sabotage on small and large companies, which are directly involved in the construction process and enrich it. A demonstration with the end point of Bässlergut, was dissolved by the cops after a failed attempt to kettle the people. However, critical discussions, information events and practical actions are not restricted, but are rather widespread. Bässlergut has become a place that brings together many people and diverse forms of resistance in order to make a fundamental criticism of current developments and social conditions. This is because the three interrelated levels of the administration of migrants in the federal camp and imprisonment in separate prisons, the increase in imprisonment penalties, and the role of humanitarian organizations, which are clearly evident in the Bässlergut project. In addition to the place where migrants arrive inside deportation prison, which in turn is connected to a corridor to the prison system. The infrastructure is co-ordinated, as is its social function: people who do not conform to the norm, who do not provide the economic bene t, or even defend themselves, are criminalized, concentrated and imprisoned. Due to the broad dimension of the developments around Bässlergut, a range of resistance forms become possible and necessary. Whether autonomous support structures, dissemination of a basic criticism, pressure on executive actors or other forms of displeasure – is important that we are loud, creative and disruptive!