Prisons are socially implicit, they seem unassailable. Throughout the political spectrum, from the left to the right, there is rarely any criticism aimed at this institution. This used to be different, prisons are a modern phenomenon. Here are some ideas which could break through this implicitness.

Even the radical left has been withdrawing their demands in the past decades. While during the 70s- and 80s the „Entknastung“1 (minimising prisons) of society was their focus point, all people dare mentioning today is the disimprisonment of „our“ political prisoners.

Prisons

Prisons have existed since antiquity, but for a long time their function differed from the function of prisons today. People were put in prisons temporarily until the proclamation of the sentence or the execution, similar to today’s imprisonment on remand.2 The punishments were monetary fines, public humiliation like the pillory or banishment, as well as corporal punishment like floggings or death penalty.

Debtor’s prisons were also very common: people were imprisoned until they settled their debts or were able to do so. This has changed: People in debt must serve their fines in prison.

Work and correction houses arose only later, in England. They were for marginalised groups and the poor so they could „improve“. From that point forward, more focus was put on punishment by incarceration as it is considered more humane than public humiliation and corporal punishment. In the 19th as well as the 20th century, there were efforts and movements to reform this system which demanded that prisons become a place for people to better themselves or be converted.

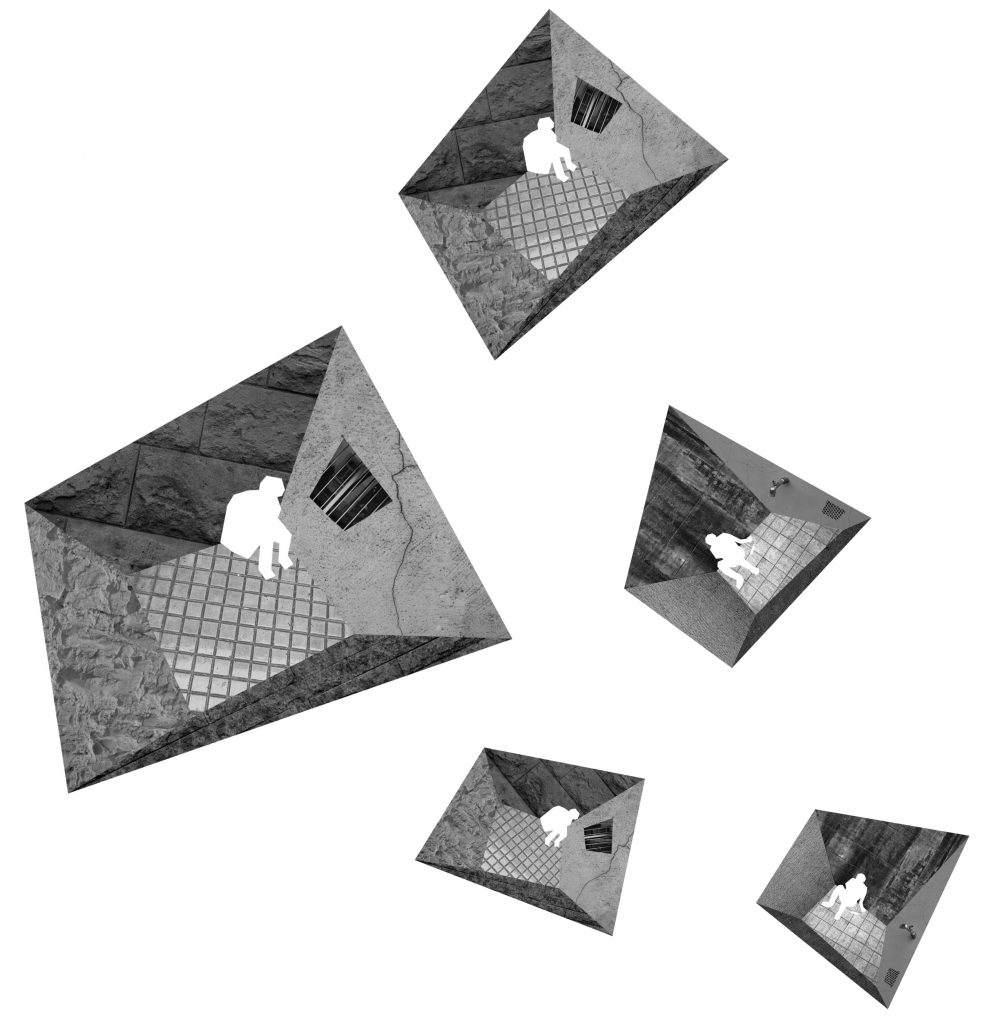

The punishment consequently disappears behind high walls from the public eye through the imprisonment. A complex, systematic correctional system with different levels of incarcerations, from adjustment of penalties, work, leave, to yard exercises and so on.

The idea remains: the body needs to reside within the building and abide by the executive power – frequently appointed by the state.

Reason 1: It creates more problems than it solves

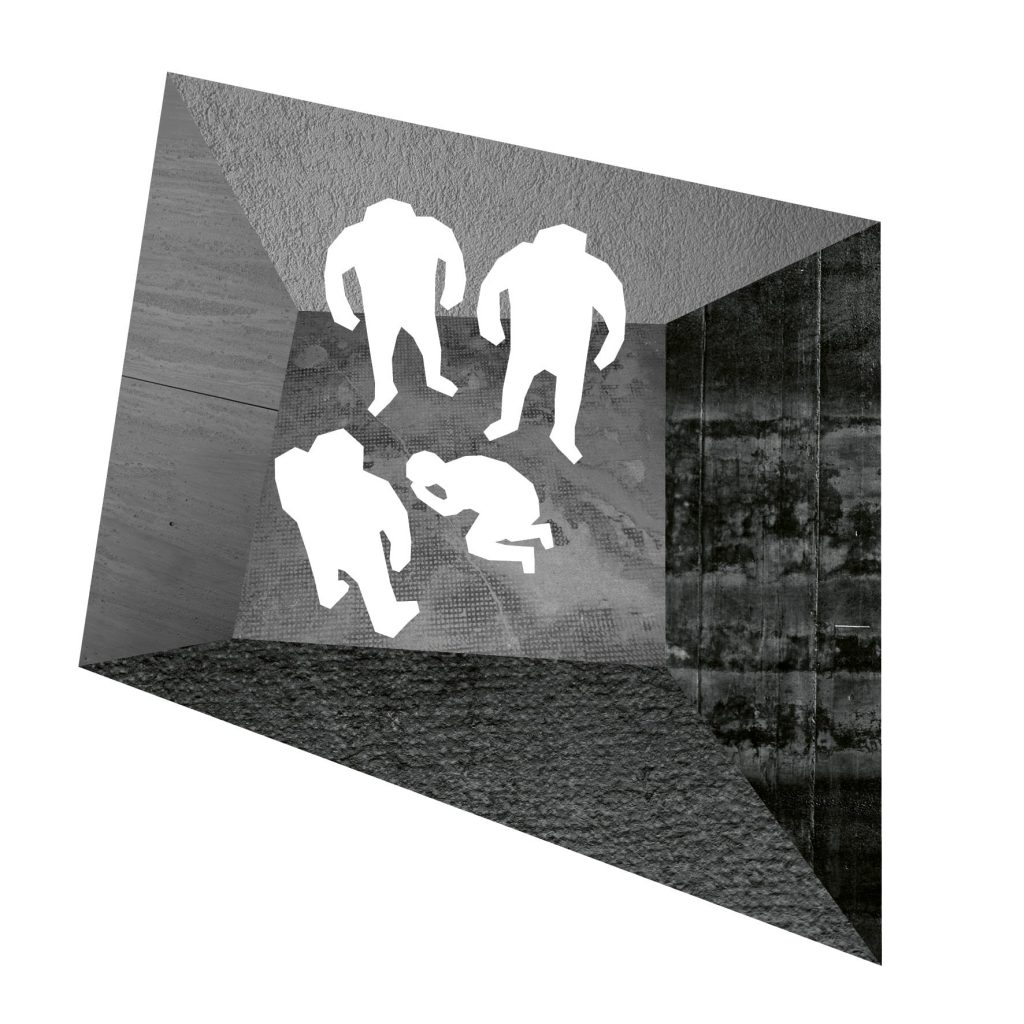

Next to the fact that a prison itself is a form of violence, many detainees become victims of violence by inmates or guards. There might be people incarcerated who are suffering from some form of trauma; it is also very likely that they will live through traumatic experiences in prison. The repressive surroundings, the hierarchical structures and living conditions enhance depression, pathological addictions, power games, and violence to and by the prisoners. For example, the highest drug prices can be found in jail.

It is absurd really that in big prisons „lawfree“ space is created, in which violence, rape, drug-trafficking etc. are on the agenda. Environments are created which make it possible to develop problematic strategies to resolve conflicts such as violence, let alone acting them out and passing them on. A prison is a place where delinquent practices and strategies are dispatched and spread. An underworld exists which hardly anyone knows let alone is interested in. It is, after all, happening behind high walls.

Many young people, who are arrested because of „small“ delinquencies, will get in contact with a environment in which delinquency is reputable and widespread. In certain cases, prison will foster the criminality it promises to fight and will do a lot of harm in doing so.

Reason 2: Society produces „superfluous people“

Prisons are full of people who came into conflict with the law through social inequality and poverty. Most of the sentences are directly or indirectly connected to questions of property. Many prisoners are users of illegal drugs. The prison, the instrument of sovereignty, is not only oppressive but just as productive: people are urged to behave productively and to conform. It is these instruments which constitute us and our society.

Many laws are part of the war against the poor. They are created to stipulate and defend the present order and existing structures (of ownership). The justice system is not as neutral and objective as it seems. What should be pursued and penalised is a political decision which so far has brought absurd dimensions (such as prison for fare evasion). Laws create a class of and legitimise delinquents and a whole apparatus of policemen and women, judges, supervision and control. Prisons, just like schools, barracks, psychiatric institutions, hospitals etc. show the individual their place in society and determine them in that exact position.

Theoretically, one of the goals of incarceration is resocialisation. The individual should take a different, more conforming position in society again. These were the goals of many reforms in the last decades. They seem to have been abandoned by now.

As long as society is as it is – full of social differences, sexism and racism – there will always be people who get into conflict with the law. Society will always produce „superfluous people“.

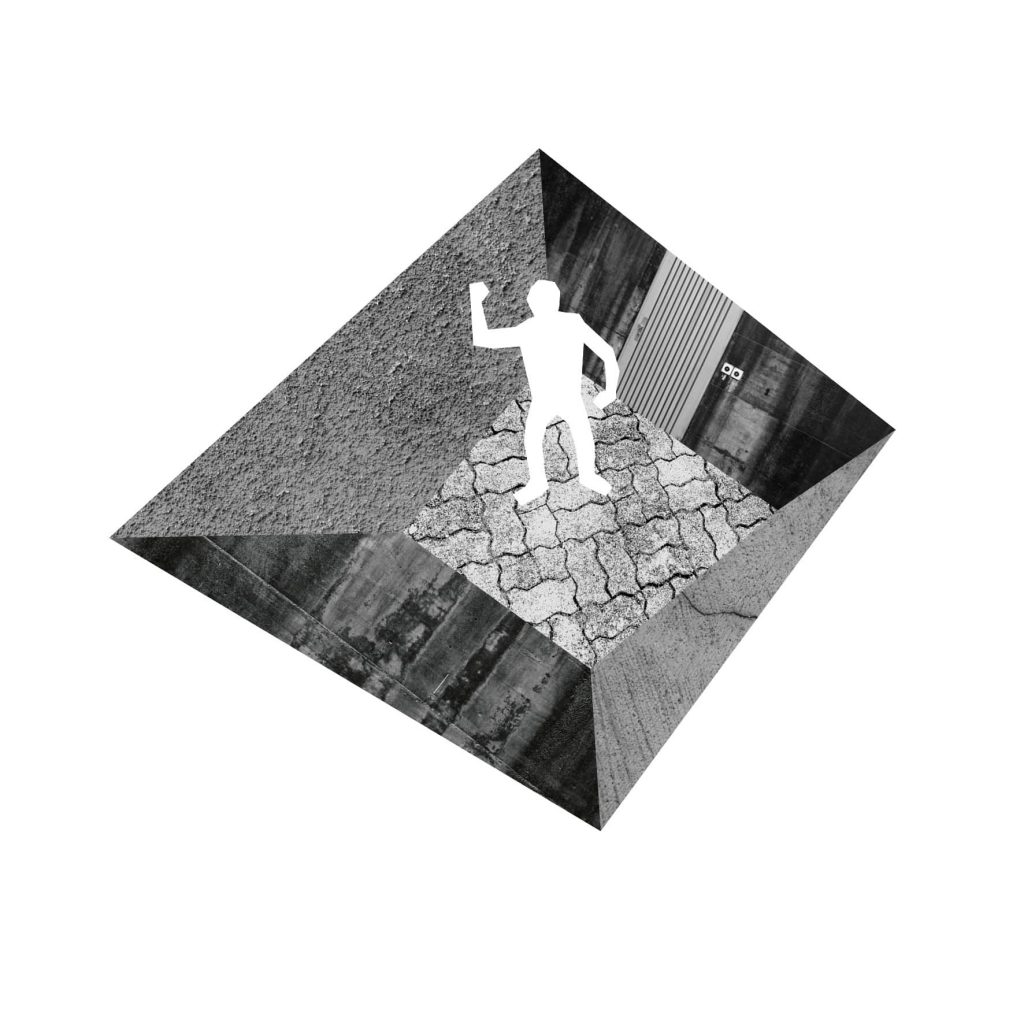

Reason 3: It should scare us

The simple awareness of prisons and prisoners should serve as deterrents. The fact that you could lose your liberty when breaking the law will make you aspire to conform and be as law abiding as possible. This fear needs to be present in our everyday life as well as our subconscious: The police in your own head. This already helps to prevent the smallest transgressions. Something that is seen as characteristic for pacified countries like Switzerland.

Reason 4: We love freedom

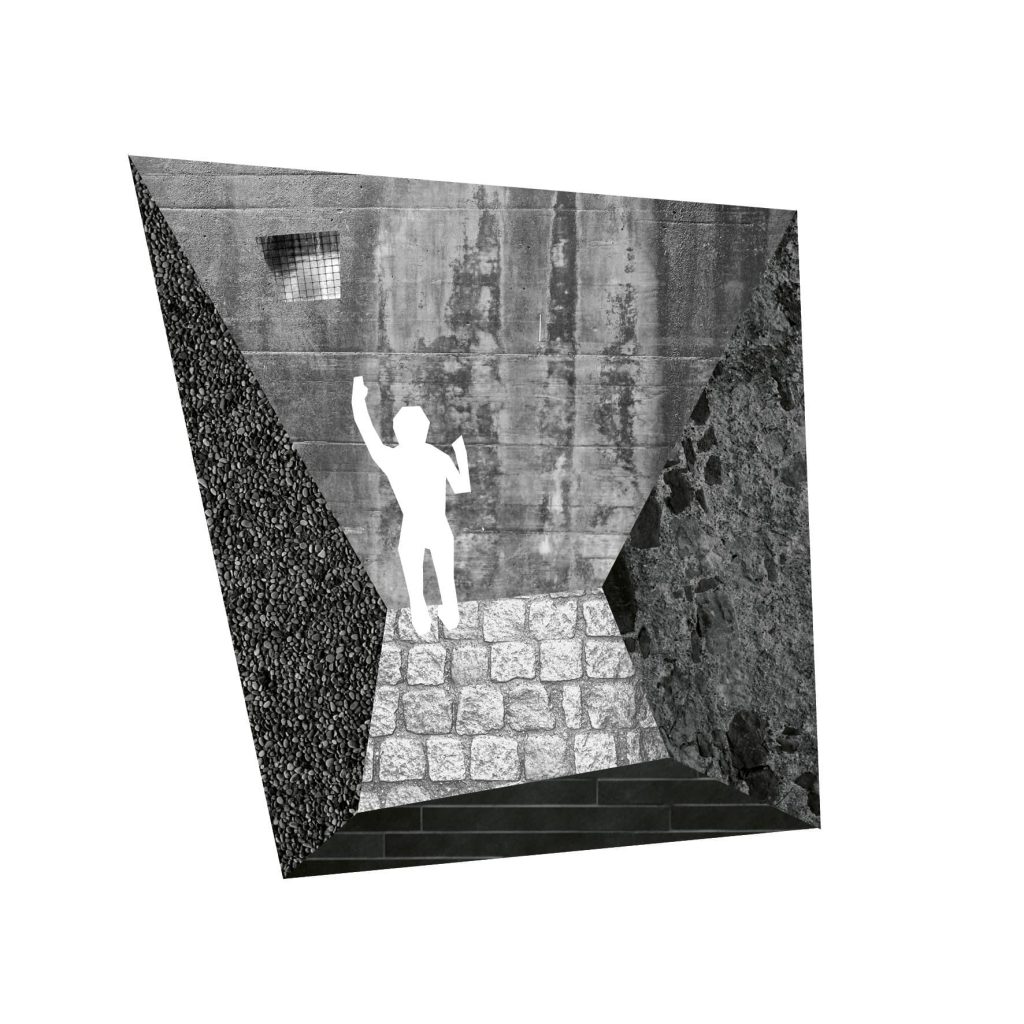

The most blatant deprivation of liberty: prisons are an especially strong form of an in- and exclusion mechanism. Resistance to and criticism of the existing order can quickly lead to imprisonment.

Reason 5: Why punish?

Is punishment a moral idea, an appropriate reaction to offences like theft, violence, or assault? Punishment always means to purposefully make someone suffer. What is the goal of making someone suffer? – The thought of punishment is based on an idea of retaliation and revenge. Delinquents are stigmatised and through this the resocialisation – which should be one of the reasons for prisons – is impeded.

The demands for severer punishments are getting louder. This is a deeply reactionary idea based on the moral concept of retaliation towards those who supposedly refuse to stick to the ruling order.

Reason 6: Sexism and racism

The people in prison are mostly men. The prisons contribute to (re)producing sexuality and gender. While men are more likely to be accused as perpetrators, women are presumed to be insane and are put into psychiatric care. Unfortunately, sexualised and racist violence are on the agenda in both institutions. The state is not able to keep its promise of security, quite the contrary: techniques and institutions like the police, prisons, borders etc. produce violence against women* and people of colour instead of stopping it.

The protection of marginalised communities is used as a pretense to have the police and the judicial system continue to resort to violence. Let us look at the example of the discussions after the incidents during the night of New Year’s Eve 15/16 in Cologne: The violence against women is a widespread and often hidden phenomenon, and is used to legitimise violence against People of Colour, in the country as well as in so-called „EU external frontiers“. If an illegalised person becomes a victim of sexual violence they might not have the possibility to turn to the police. They could experience violence once more: they could be incarcerated and deported.

Community based approaches

So how to feel safe if there were no prisons and the police are of no help?

There are some approaches from queer-feminist circles which have already been applied many times with mixed results. The idea is that the environment of the perpetrator and the environment of the „victim“ can try to find a way to handle the experiences of the „act“ and to understand and work out the consequences. Many of us have certainly done that with small offences, assaults and problems in the social environment. The following principles have been worked out by people who have worked on this topic extensively.3

- Collective support, security and self-determination for the affected people.

- Responsibility and change of habits of the person who used violence.

- Development of the community towards values and practices directed against violence and oppression.

- Structural and political change of the conditions which have made violence possible.

Consequently, the people using violence are offered the possibility to change their behaviour instead of being punished and cast off. It is more about empowering the people affected by the violence instead of just protecting them. The “victim’s” self-determination needs to be reclaimed and they should not just receive protection from the outside as a „powerless“ person. This strategy is at the core of the assumption that the people who have been affected by violence have great knowledge and skills that will make them into potential participants of their own as well as societal change.

This is an entirely different approach than prisons are, which want to sell us security through the safekeeping of danger. This prison-logic tries to isolate a few „rotten apples“. But often there will be good explanations 4, albeit no excuse for violence.

All these approaches are only possible if the people have social environments that are stable enough, and see themselves able to act and intervene in a violent situation. To make this possible for all people we most likely need to live in a different world. The reasons for a fight against prisons do not only have to do with criminal justice and the state but are also questions about an emancipated and just world.