I am 30 years old, originally I come from Guinea Conakry and now I live and work in Basel. Ten years ago I have been forced to leave my country because of the dictatorship and family problems. My journey from Guinea to Switzerland took almost eight years – here I can draw a rough sketch:

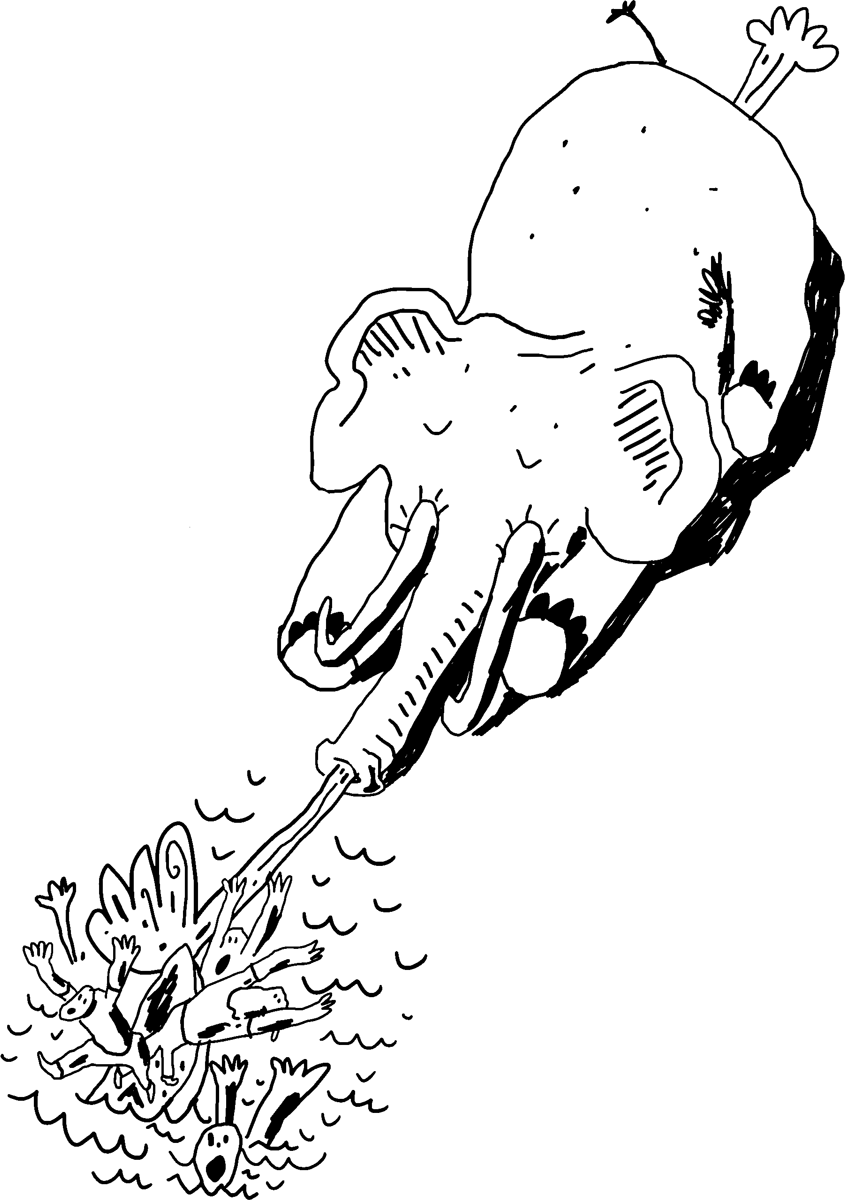

I left Guinea in December 2006 to Senegal, and then went on to Mali, Niger and Libya, where I did arrive three months later. It was a journey through the dessert and through hell – not every- body of our group did come through. Arriving in Libya I realised, that there were a lot of problems with the police. People could not go out how they wanted. My passport was ripped and I was put in prison for 3 months near Tripoli. In this time I was tortured and abused – I and many other Africans were suffering a lot. But going back through the dessert was not an option; I would not survive it again.

When I was out of prison and arrived in Tripoli it was so hard to get a job and also to get a help when you are sick. Because if you try to go to the hospital they will call the police to arrest you. That’s why many migrants were suffering a lot. Sometimes in the night the police tried to come also into the houses to arrest people. I saw a lot of men, women and children, who always got abused. This is why I think, that Europe doesn‘t have the right to send back people to Libya. And since I was there, it got even more dif cult than before, when Gadha had the power.

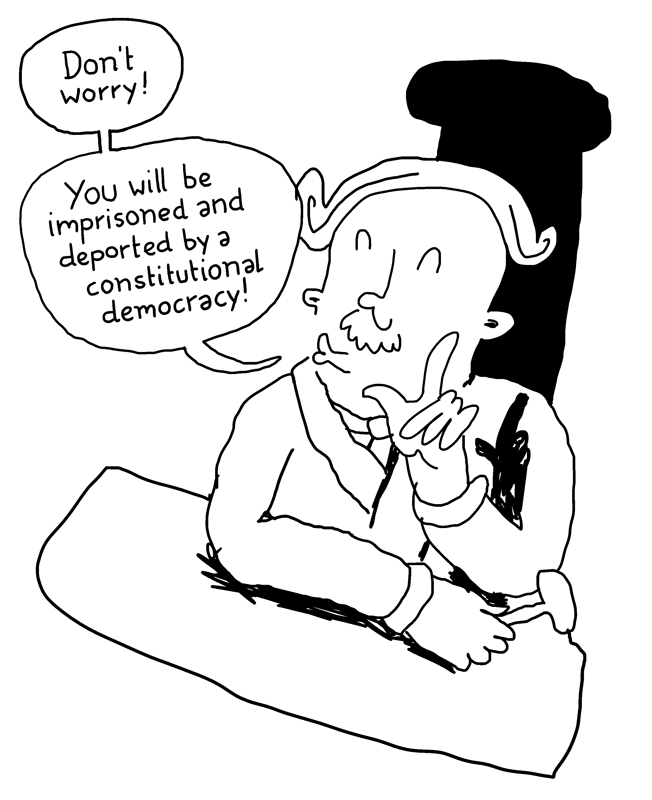

I decided to leave Libya and the only possible way was by boat. The rst attempt did end in a disaster – many people died. The second journey took us ve days on the sea. I arrived in Malta on the 18th august 2007 with other 28 people. In Malta the police arrested us and brought us to a detention-center called Alhalfar. In this prison I had to stay for one year, some others were there for one and a half year. Only Africans are treated like this in Malta – others are deported directly back to their countries, others are allowed to live in a camp. The official statement to justify imprisonment is that west Africans can be vectors of infectious diseases and therefore they have to be isolated. The bad thing in the detention-center was that we were not informed what’s going on with us, how long we have to stay there and why we were arrested.

To organize ourselfs is something which is positive, if it‘s happening. But it‘s not easy. Because we as groups are being separated.

I had the very big problem that I couldn’t sleep at night because of worst nightmares. But when I could meet the doctor and tell him about my problem, he always gave me a sleeping tablet. That was not good at all, because even with medicaments you wake up with horrible pictures, you cannot sleep anymore but however you feel weak and powerless. There was also another big problem; there was no translator at all. In that center there was more than one at and every at had three rooms. There were two toilets for over 500 people and we had one TV.

After leaving the center I was working in a hospital for nine months. Because I realized, that I will not get help in Malta to be- come healthy again, I decided to go to Italy. Arriving in Italy they did let me know, that I have to go back to Malta, because I had my rst ngerprints over there (Dublin contract within the EU).

So I had to continue the journey and in November 2009 I did ar- rive in the Netherlands. That was the rst time I discovered that I had a trauma. They did send me to a psychologist doctor and I got the help I needed. I was given medicine and I was sent to school – I learned how to read and write. After two and half year stay in Holland they evaluated me to be a healthy person and sent me back to Malta on the basis of the same Dublin contract.

Arriving in Malta I was put in prison again, because I went out of the country without a passport or any permission. I was im- prisoned another 6 months. After all of this I decided to learn from the past and to share my experience with other migrants, to help them to orient in the new culture, system and society. Ano- ther aim is to inform young people in Africa about migration to Europe and not to leave the school and study a lot to get a good education. So they can grow up in their own countries, change their country for the better and do not have to risk their lives and dignity on the dangerous ways to Europe.

To organize ourselves is something which is positive, if it’s hap- pening. But it’s not easy. Because we as groups are beeing se- parated. For example the Senegalese and the Guinean, or the Nigerians and the Ghanaians, they will not go together. This is a big problem. If you will be able to break this problem between these groups, things could go better. In Malta three main categories of migrants are made – people from

Near-East countries, from East-Africa and from West-Africa. Everyone has different chances to get a legal status. So the East-Africans (who has better chances) will not join the West-Africans (who have almost no chance) to fight against the problems. Only West-Africans are trying to organize themselves. And also within the West-Africans

maybe there are five out of thousand, who know the situation, the people, the country,

so they will not join because they’re afraid to lose their benefit. Furthermore you need to have a specific place where to stay. I remember for example when we were trying to organize a meeting to discuss the humanitarian temporary. We were in a stadium where you can play football. The first meeting was good; we had a lot of people joining in. During the second and third time, there was already police there. Since the police showed up, people didn’t come to the meeting.

In Europe, I was educated; I learned about my rights, I learned that here is some more equality and that one can fight for ones rights. In Malta I went about setting up a Facebook page under the name “R. Know More Network” and then proceeded to roam the open centers, speaking to migrants about the importance of educating themselves and learning about the local culture. The ‘R’ stands for my mother’s name, Ramatah. Many Africans have a tendency of keeping inside the feelings, problems and troubles they have and do not speak about their experience. But we need to tell the Europeans who we are and why we left our home country for them to understand.